Adaptive–mitigative (or mitigative–adaptive)

Narrative

Over the past 25 years of integrating environmental and sustainability issues into the making of cities, thinking has largely followed a sequential logic: energy first, then carbon, and now adaptation. 2022 marked a turning point. Its deadly summer accelerated everything—repeated heatwaves, droughts, water stress, forests pushed to their limits, megafires, collapsing agricultural yields, soaring energy costs… There is a clear before and after.

Adaptation has finally taken its place in projects, narratives and public policies. It has become tangible, urgent, material.

But beware of replacing one dogma with another: as necessary as adaptation may be, it must never override mitigation. If we do not do everything in our power to reduce our impacts, even the best adaptation strategies will prove futile. Because we do not adapt to a +7°C world. Or only some of us do—and not without dramatic consequences.

The shift is subtle, but very real. Politically, adaptation is easier to promote: it addresses local, visible, immediate vulnerabilities. Planting a tree, depaving a street, restoring comfort—these actions are concrete, measurable, popular. And above all, they fit within the timeframe of an electoral mandate. Mitigation, by contrast, operates over the long term, for the benefit of other territories and future generations. Decarbonising means investing in a future we do not fully control. In a fragmented world, such distant promises struggle to mobilise.

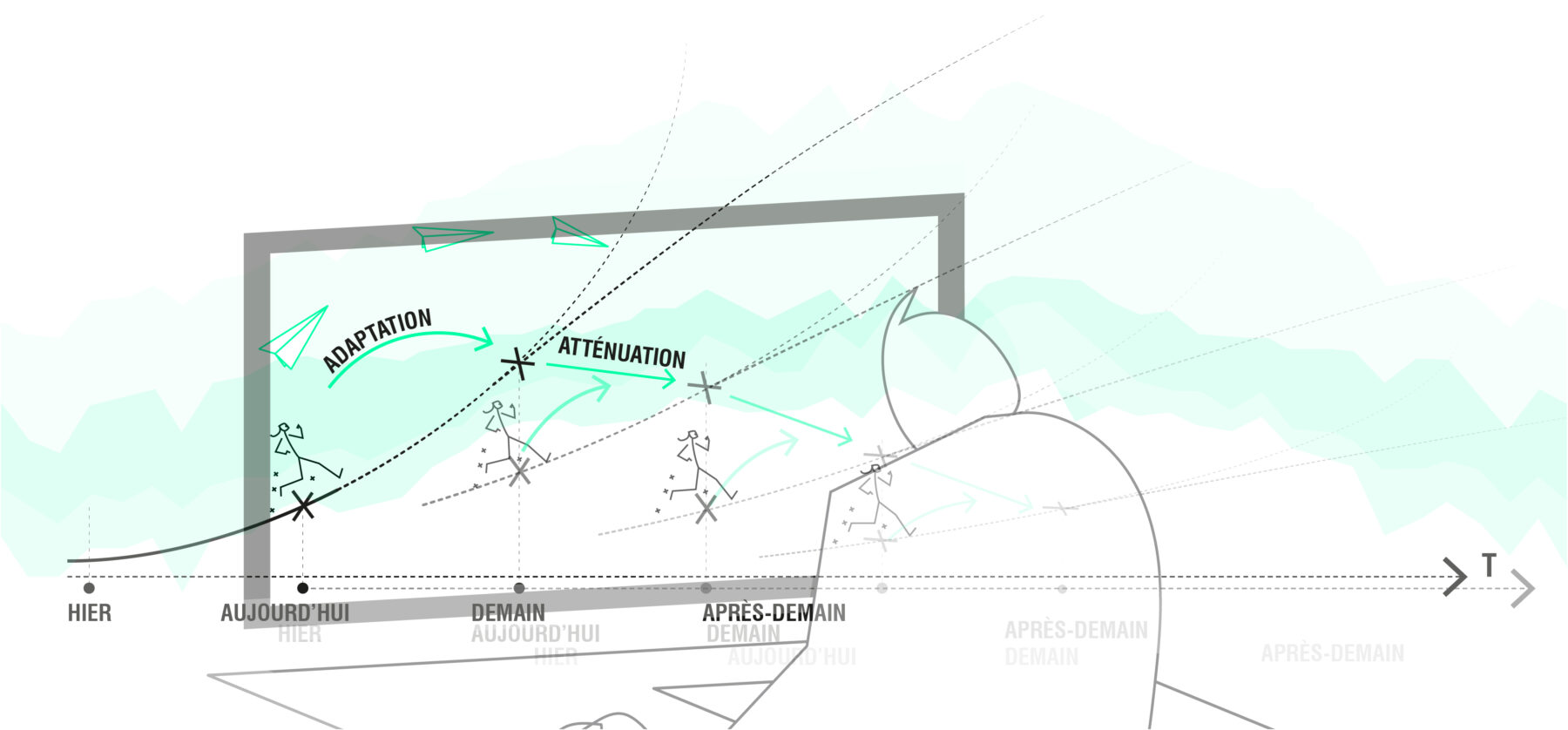

This is precisely where adaptive–mitigative strategies come into play: articulating immediate adaptation with the structural reduction of impacts. Thinking of projects as a dual response—absorbing shocks while reducing their root causes.

The city of the future is already here: 80% of the buildings that will exist in 2050 already stand today, and almost none of them are suited to the climates ahead. Urban renewal is too slow, demographic growth too weak, resources too scarce. New construction is no longer the norm; it has become the exception.

Rehabilitation therefore becomes the rule—not by default, but by coherence. Existing buildings have already amortised their carbon debt. The objective of zero net land take reinforces this logic. Reusing what already exists is a carbon, spatial and territorial strategy. But it still has to be done properly. Rehabilitate, yes—but without excessive recarbonisation. Without erasing the climatic qualities of existing buildings. Without sacrificing the balance between energy use (flows), materials (stocks) and comfort (use).

This is where the core of adaptive–mitigative strategies lies. Not in opposition, but in articulation. Not in choosing between prevention and absorption, but in the ability to do both at once.

Well-designed adaptation is a political project.

It engages elected officials, residents and designers.

It is social, territorial and democratic.

But it will only endure if it is accompanied by a collective effort to sustainably reduce our impacts.

Adapt to endure. Mitigate to last.

This is the only sustainable pathway.

Contribution

From the book "Les 101 Mots de l'Adaptation, à l'usage de tous", under the direction of Atelier Franck Boutté

Title

Adaptive–mitigative (or mitigative–adaptive)

Author

Franck Boutté, President, and Elise Lenoble, communication manager at Atelier Franck Boutté

Editor

Archibooks

Publication date

2025

Pages

176 pages

Illustration

Sébastien Hascoët