The Common as Project

Narrative

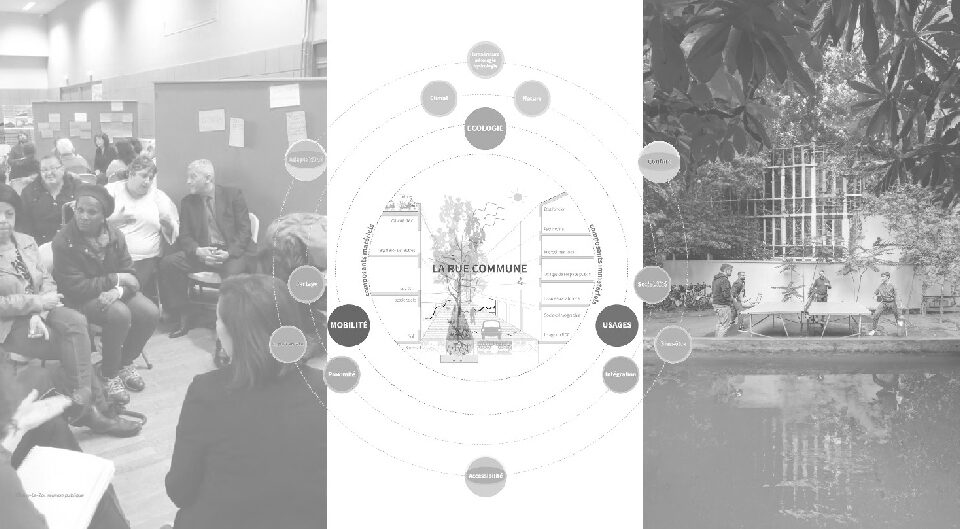

Transforming the Collective

In the early 2000s, the “classic” apartment block was designed “on one lot”: a more or less square footprint, with four corner dwellings supposedly offering “cross through” ventilation—meaning dual aspect at best, which is not at all the same thing. In the center of this layout, the common area, often steep and dark, was concentrated around the elevator all the way down to the first floor.

Picture arriving in such a building. After leaving your vehicle in the car park, you take the elevator to the floor where you live. When the doors open, you step out on to a landing in pitch darkness, an anxiety-inducing experience that can make the everyday act of encountering a neighbor feel like a potential run-in with a serial killer. You finally get to the switch, but no sooner have you struck up a friendly conversation with your immediate neighbor (totally harmless it turns out) than 30 seconds later, the automatic timer on the light switch plunges you back into the dark. So you switch the light back on. Flicking the switch five times in a row just to be cast in artificial light—no flood of natural light the way this building is designed—quickly becomes boring and so the conversation is cut short... It’s precisely this type of collective living that kills the joy of communal living and ironically promotes the desire to live alone.

It’s vital to focus on the essential when it comes to the common areas, those shared spaces that can, precisely, become the place for community. The design should, at a minimum, include a naturally lit landing, providing a spacious and appealing primary circulation area, treated as a living space. This is a more typical consideration today but it needs to become even more widespread. Occupiers will certainly feel more keen to stop, talk, and create common stories. This will eventually encourage residents to meet their neighbors, chat with them, and build something together, thus creating a common future.

Once again, striking a balance is of paramount importance. It’s clear that we have to take into account the notion of sobriety in any design, and thus consider the right balance between private and common spaces, between useful and superfluous square footage. If we try to make all the spaces bigger, it won’t work. But it is important to foster a collective that rouses the desire to love community and ultimately provides a sense of collective belonging.

The question of common spaces arises as well, and more importantly, in suburban areas. With 55% of existing housing in France composed of single-family homes, it is imperative to address the issue of common living and shared spaces in these residential neighborhoods.

More broadly, any program, even if it is individual, has a “common” dimension that is too often not given enough thought. To fight against our falling out of love with cities and urban sprawl, it is essential we promote a sense of collective that reawakens our want and desire to live in a community.