Thermal confort

Narrative

When it comes to adapting regions to global warming, “thermal comfort” is a key issue. It is now a central concern in urban planning, although the term is often used imprecisely: sometimes to refer to related issues, such as thermal comfort or health risks, and sometimes mistakenly as a consequence of reducing the “urban heat island” effect.

These semantic shifts are encouraged by the complexity of the concept, which covers several approaches and definitions. Functionally, thermal comfort is one of the determinants of an individual's well-being, influencing the use of urban spaces according to their microclimatic conditions. Psychologically, it is defined by the ANSI/ASHRAE 55 (2020) standard as the state of mind expressing satisfaction with the thermal environment. Finally, from a thermophysiological perspective, it corresponds to thermal neutrality, in which the body is able to dissipate the excess heat produced by its metabolism. This balance depends on individual characteristics (age, gender, body type, activity level, type of clothing) and environmental parameters (air temperature, humidity, ventilation, radiation). This is one of the distinctions with the heat island, which is not very representative of thermal comfort, as it is limited to the analysis of air temperature alone. Thus, in a heatwave situation, thermal comfort may be better in a place where the air is warmer than elsewhere if the other microclimatic parameters are more favorable.

To objectively measure thermal comfort, there are more than 200 thermal comfort indicators, such as UTCI and PET, which reflect actual thermal perception: the “comfort” zone represents only the range corresponding to an individual's optimal thermal comfort. Thus, in hot climates, “improving comfort” in practice means reducing the value of these indicators, since their increase reflects an intensification of the sensation of heat.

Furthermore, the issue of thermal comfort could be reduced to a binary approach—either I am comfortable or I am not. However, in practice, when a community or developer commissions a thermal comfort study, particularly during heat waves when comfort will not be achieved, what they are actually expecting is a more detailed analysis, corresponding to an assessment of thermal perception in all its nuances: mapping stress levels in space, identifying critical areas of existing urban heritage, and quantifying the mitigation of thermal stress on residents through urban projects to be carried out. These approaches also aim to identify areas posing a health risk, even though thermal comfort was not designed to quantify this risk.

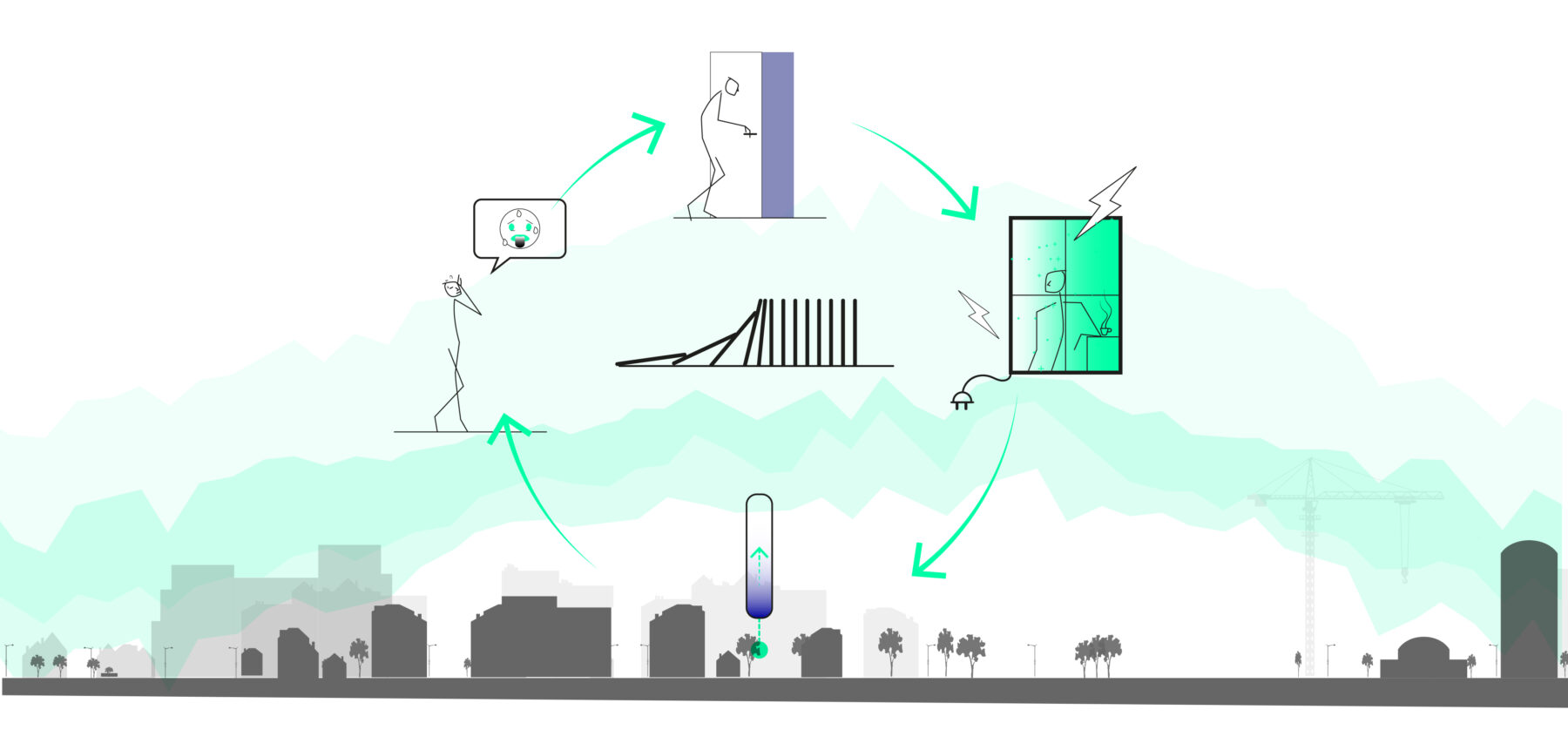

In conclusion, even if the term is misused, the approaches grouped under the label of “thermal comfort”—extension of comfort zones, reduction of thermal stress, limitation of health risks—remain essential for the adaptation of cities. Indeed, the deterioration of outdoor comfort triggers a domino effect: worsening microclimatic conditions cause residents to retreat indoors, where increased use of air conditioning releases heat outside, further aggravating microclimatic conditions. This is why improving the thermal environment in public spaces is a priority for preserving the livability of cities, while limiting the anthropogenic factors that exacerbate urban overheating.

Contribution

From the book "Les 101 Mots de l'Adaptation, à l'usage de tous", under the direction of Atelier Franck Boutté

Title

Thermal confort

Author

Matteo Migliari, lead consultant at Atelier Franck Boutté

Editor

Archibooks

Publication date

2025

Pages

176 pages

Illustration

Sébastien Hascoët