From Geography to the Intimate

Narrative

Summer Comfort: A Traveling Story

We know that summer comfort, both in buildings and outdoor spaces, is one of the major challenges of the future. To address this, two basic elements are key: protecting oneself from the sun and utilizing the wind. In the past, people would soak a cloth in a basin of water before placing it in front of an open window—using the cloth as a heat exchange surface, water as an element that absorbs energy when it changes state, and the wind as the driving force. These are the three ingredients of an adiabatic cooler.

In cities today, the principle remains largely the same. We work with the same three conditions: the exchange surface—often vegetation—water, which is drawn up from the ground by plants and released through evapotranspiration, and the wind. However, this resource must be available in the first place…

The Role of Urban Space

When you open a window in a home, what happens? Maybe nothing. Because the breeze comes from elsewhere—it doesn’t just exist right behind the window. It is not an instantly available resource; rather, it originates from open spaces, streets, the public domain, and the urban fabric.

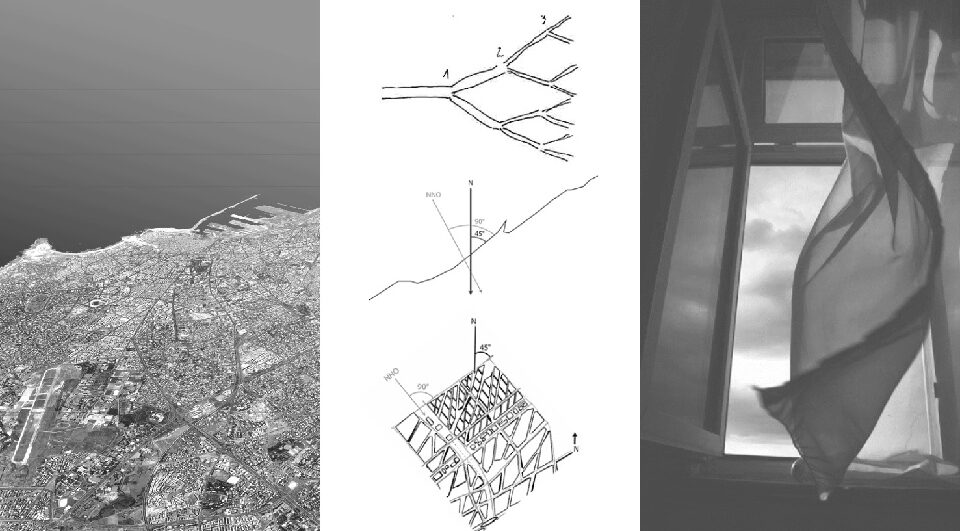

Let’s zoom out—perform a traveling shot backward—all the way to geography: what does this window overlook? Is the public space it opens onto vegetated? Is there water? Is its orientation compatible with prevailing winds? How is the city organized, and what is its position within its broader territory, its watershed, its geography? Has the wind first passed over a cooling mass, such as vegetation or a body of water? Or has it been warmed by crossing highly mineralized areas? This raises questions not only about the shape but also the nature of the city’s open spaces and their connections. Beyond these connections, there are also issues of climatology, meteorology, and ultimately geography, all of which shape and define whether a resource like wind is actually available just beyond a window.

Thus, the urban framework—primarily designed today to accommodate car traffic—must also be considered from this perspective: is the street connected to larger streets that themselves have managed to capture the wind? How permeable is the city to the open spaces surrounding it? Are these open spaces themselves cooling areas? What happens when a window is opened depends, in part, on these factors.

Sometimes, a building or a continuous built frontage obstructs wind circulation. In such cases, demolitions or openings can provide significant benefits, naturally re-ventilating an entire neighborhood.

Architecture and Ventilation

However, having the wind arrive at a window does not guarantee it will enter a building. If we now zoom in—perform a traveling shot forward—other architectural and interior design questions arise: How thick is the building? Is it cross-ventilated, and if so, what does the opposite window open onto? Can it be opened?

Next, the organization of the living space itself must be examined: does it allow for the necessary air permeability to enable breeze circulation indoors? In other words, is there a spatial division—such as a separation between day and night areas—that disrupts the airflow?

Perhaps rooms should be designed to run from one facade to another, or ventilation shutters should be integrated into walls and doors, as seen in Le Corbusier’s La Tourette convent.

The question of the breeze as an ally for summer comfort raises issues across all scales—from geography to interior spaces, from urban planning to architecture—demanding a scalar coherence that requires all stakeholders to design collectively.